De last van lymeborreliose

Door: Leo Pruimboom

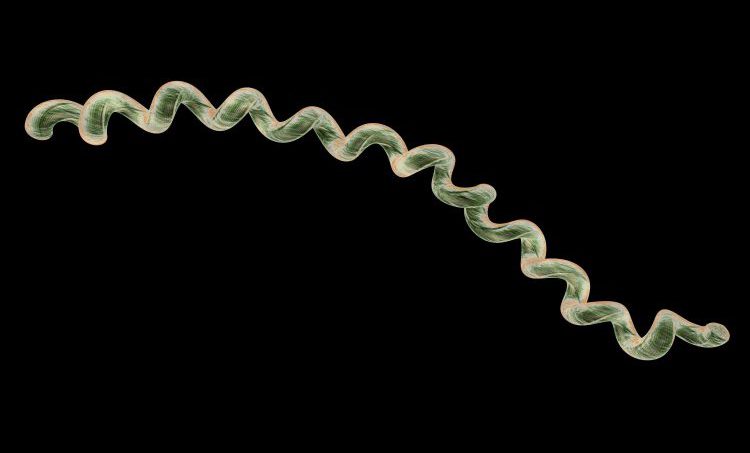

De epidemiologie van de Borrelia-infectie is momenteel een van de meest zorgwekkende onderwerpen wereldwijd, met een jaarlijkse incidentie van 350.000 nieuwe patiënten in de Verenigde Staten en ongeveer 85.000 in Europa3. De daadwerkelijke prevalentie van de ziekte van Lyme wordt geschat op 500.000 ziektegevallen. Dit brengt naast de enorme ziektelast ook kosten met zich mee; voor de Verenigde Staten naar schatting vijf miljard dollar per jaar.4

Preventie is vooralsnog de beste manier om lyme te behandelen5. Hoe de Borrellia-infectie verloopt, is afhankelijk van verschillende factoren, waaronder leeftijd, geslacht, vitamine-inname, voedingsstatus en rookgedrag.6 Leeftijd en de periode van het jaar zijn geassocieerd met een hogere incidentie van de Borrelia-infectie, wat hoogstwaarschijnlijk veroorzaakt wordt door het hoge aantal bezoeken aan het bos in de maanden juni en juli door mensen van rond de 45 jaar.7

Heeft men de infectie eenmaal opgelopen, dan is vroege diagnose en een behandeling met antibiotica bij uitstek de meest effectieve aanpak.7 Een late diagnose vermindert de effectiviteit van een behandeling met antibiotica en vraagt om meer geavanceerde strategieën, waarbij antibiotica wordt gecombineerd met natuurlijke verbindingen zoals vitamine D8, baicalein (een polyfenol uit Scutellaria baicalensis), luteoline (een gele polyfenolkleurstof voorkomend in verschillende groenten)9, lactoferrine10 en N-acetyl-cysteïne.11 Helaas reageert tien tot twintig procent van de aangedane patiënten niet op een relatief vroege behandeling en ontwikkelt Post Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome (PTLDS). Typische symptomen bij de groep mensen met PTLDS zijn vermoeidheid, intermitterende koorts, koude rillingen, spier- en gewrichtspijn.12

Lees het gehele artikel vanaf pagina 12 in OrthoFyto 4/18.

Klik hier om de vragen lijst van Horowitz te openen.

- Steere, A. C., Malawista, S. E., Snydman, D. R., Shope, R. E., et al. Lyme arthritis: an epidemic of oligoarticular arthritis in children and adults in three connecticut communities. Arthritis Rheum 20, 7-17 (1977).

- Burgdorfer, W., Barbour, A. G., Hayes, S. F., Benach, J. L., et al. Lyme disease-a tick-borne spirochetosis? Science 216, 1317-1319 (1982).

- Schotthoefer, A. M. & Frost, H. M. Ecology and Epidemiology of Lymeborreliosis. Clin Lab Med 35, 723-743 (2015).

- Berry, K., Bayham, J., Meyer, S. R., & Fenichel, E. P. (2017). The Allocation of Time and Risk of Lyme: A Case of Ecosystem Service Income and Substitution Effects. Environmental and Resource Economics, 1–20.

- Lyme Disease. Lyme Disease. Centre for Disease Control. (n.d.). Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- Oosting, M., Kerstholt, M., Ter Horst, R., Li, Y., et al. Functional and Genomic Architecture of Borrelia burgdorferi-Induced Cytokine Responses in Humans. Cell Host Microbe 20, 822-833 (2016).

- Steere, A. C., Strle, F., Wormser, G. P., Hu, L. T., et al. Lymeborreliosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2, 16090 (2016).

- Donta, S. T. (2012). Issues in the diagnosis and treatment of lyme disease. The Open Neurology Journal, 6, 140–5.

- Goc, A., Niedzwiecki, A. & Rath, M. Cooperation of Doxycycline with Phytochemicals and Micronutrients Against Active and Persistent Forms of Borrelia sp. Int J Biol Sci 12, 1093-1103 (2016).

- Lusitani, D., Malawista, S. E. & Montgomery, R. R. Borrelia burgdorferi are susceptible to killing by a variety of human polymorphonuclear leukocyte components. J Infect Dis 185, 797-804 (2002).

- Dinicola, S., De Grazia, S., Carlomagno, G. & Pintucci, J. P. N-acetylcysteine as powerful molecule to destroy bacterial biofilms. A systematic review. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 18, 2942-2948 (2014).

- Pothineni, V. R., Wagh, D., Babar, M. M., Inayathullah, M., et al. Identification of new drug candidates against Borrelia burgdorferi using high-throughput screening. Drug Des Devel Ther 10, 1307-1322 (2016).

- Feder, H. M., Johnson, B. J. B., O’Connell, S., Shapiro, E. D., Steere, A. C., Wormser, G. P., & Group, the A. H. I. L. D. (2007). A Critical Appraisal of ‘Chronic Lyme Disease’. New England Journal of Medicine, 357(14), 1422–1430.

- Nemeth, J., Bernasconi, E., Heininger, U., Abbas, M., et al. Update of the Swiss guidelines on post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome. Swiss Med Wkly 146, w14353 (2016).

- Rebman, A. W., Bechtold, K. T., Yang, T., Mihm, E. A., et al. The Clinical, Symptom, and Quality-of-Life Characterization of a Well-Defined Group of Patients with Posttreatment Lyme Disease Syndrome. Front Med (Lausanne) 4, 224 (2017).

- Troxell, B., & Yang, X. F. (2013). Metal-dependent gene regulation in the causative agent of Lyme disease. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 3, 79.

- Tilly, K., Rosa, P. A. & Stewart, P. E. Biology of infection with Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Dis Clin North Am 22, 217-34, v (2008).

- Gern, L., Estrada-Peña, A., Frandsen, F., Gray, J. S., et al. European reservoir hosts of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato. Zentralbl Bakteriol 287, 196-204 (1998).

- Fraser, C. M., Casjens, S., Huang, W. M., Sutton, G. G., et al. Genomic sequence of a Lyme disease spirochaete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Nature 390, 580-586 (1997).

- Horowitz, R. I. (2016). Approach to diagnosing Lyme disease misses a large proportion of cases. BMJ, i113.

- Tracy, K. E. & Baumgarth, N. Borrelia burgdorferi Manipulates Innate and Adaptive Immunity to Establish Persistence in Rodent Reservoir Hosts. Front Immunol 8, 116 (2017).

- Malawista, S. E., & de Boisfleury Chevance, A. (2008). Clocking the Lyme Spirochete. PLoS ONE, 3(2), e1633.

- Önder, Ö., Humphrey, P. T., McOmber, B., Korobova, F., et al. OspC is potent plasminogen receptor on surface of Borrelia burgdorferi. J Biol Chem 287, 16860-16868 (2012).

- Mead, P. S. Epidemiology of Lyme disease. Infect Dis Clin North Am 29, 187-210 (2015).

- Gebbia, J. A., Coleman, J. L., & Benach, J. L. (2004). Selective Induction of Matrix Metalloproteinases by Borrelia burgdorferi via Toll‐Like Receptor 2 in Monocytes. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 189(1), 113–119.

- Tracy, K. E., & Baumgarth, N. (2017). Borrelia burgdorferi Manipulates Innate and Adaptive Immunity to Establish Persistence in Rodent Reservoir Hosts. Frontiers in Immunology, 8, 116.

- Aslam, B., Nisar, M. A., Khurshid, M. & Farooq Salamat, M. K. Immune escape strategies of Borrelia burgdorferi. Future Microbiol 12, 1219-1237 (2017).

- Wolgemuth, C. W. (2015). Flagellar motility of the pathogenic spirochetes. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology, 46, 104–12.

- Moriarty, T., and M. Norman. Real-Time High Resolution 3D Imaging of the Lyme Disease Spirochete Adhering to and Escaping from the Vasculature of a Living Host. PLOS ONE, 20 June 2008. Web. 25 Apr. 2016.

Bronvermelding:

Bronvermelding:

OrthoFyto

Verzameling van artikelen van schrijvers die op niet-regelmatige basis voor ons schrijven.